Now Reading: After a 21-year-old migrant was murdered, her body parts were harvested as her family fought to bring her home

-

01

After a 21-year-old migrant was murdered, her body parts were harvested as her family fought to bring her home

After a 21-year-old migrant was murdered, her body parts were harvested as her family fought to bring her home

This article is part of “Dealing the Dead,” a series investigating the use of unclaimed bodies for medical research.

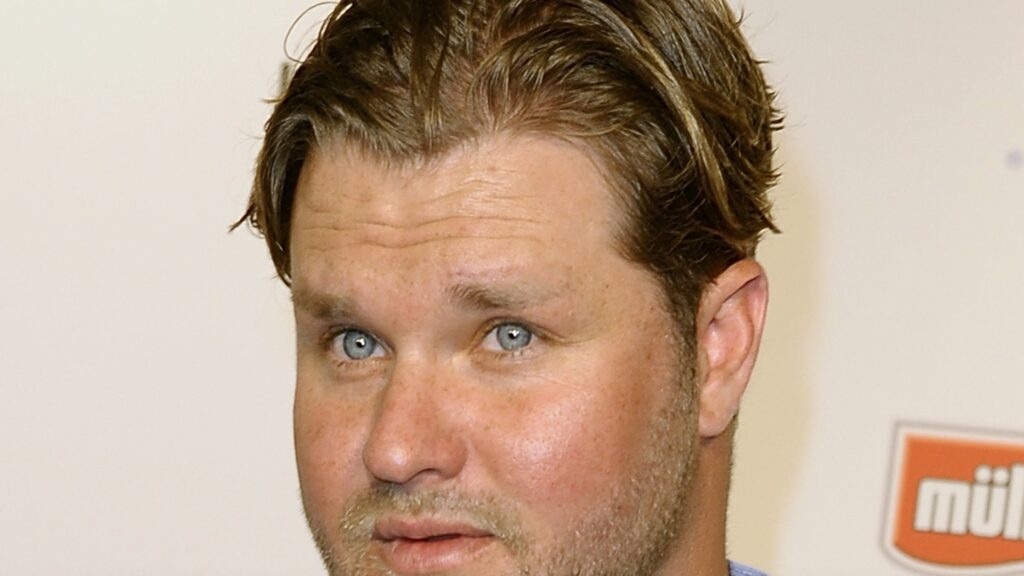

Every day for two seemingly endless months, Arelis Coromoto Villegas repeated the same prayer: From her small, cinder-block home in Venezuela, she asked God to protect her 21-year-old daughter as she trekked thousands of miles through treacherous jungle and desert terrain to reach America’s southern border.

Her prayers were answered in September 2022 when Aurimar Iturriago Villegas crossed safely into the U.S. and continued north with her own prayer — to land a job and eventually earn enough money to help her mother build a new house.

But within two months of her arrival in Texas, Aurimar was dead, shot in a road rage incident near Dallas as she sat in the back seat of a car.

And then, for her mother, the unthinkable somehow became the unimaginable.

Without her family’s knowledge, county authorities donated Aurimar’s body to a local medical school, where officials cut it up and assigned dollar figures to parts that hadn’t been damaged by the bullet that struck her head — $900 for her torso, $703 for her legs.

Remnants of Aurimar’s body were cremated and buried in a field among strangers in a Dallas cemetery, all while her mother desperately sought to have her murdered daughter returned to Venezuela, unaware her body had become a commodity in the name of science.

Arelis only learned her daughter had been used for research two years after her death, when NBC News and Noticias Telemundo — as part of a broader investigation of the U.S. body industry — published the names of hundreds of people whose unclaimed bodies were sent to the Fort Worth-based University of North Texas Health Science Center.

“It’s a very painful thing,” Arelis said in Spanish, in an interview from her home in a small town in western Venezuela. “She’s not a little animal to be butchered, to be cut up.”

What happened to Aurimar was a matter of money, part of a pattern NBC News uncovered over the past two years: Across the United States, vulnerable people’s bodies often are mistreated and their families’ wishes disregarded as overwhelmed local officials grapple with rising numbers of unclaimed dead amid widespread opioid addiction, surging homelessness and increasingly fractured families. Reporters found that county coroners, medical institutions and others repeatedly failed to contact reachable family members before declaring bodies unclaimed.

In some cases, people were buried in paupers’ fields as their loved ones reported them missing and searched for them. In others, corpses were sent to medical schools, biotech companies and for-profit body brokers without consent.

Aurimar was one of about 2,350 people whose bodies were sent to the University of North Texas Health Science Center since 2019 under agreements with two local counties, which helped the center bring in about $2.5 million a year and saved the counties hundreds of thousands of dollars in cremation and burial costs, according to financial records.

Hundreds of the bodies were used for student training or research. Others were leased out to medical technology companies that require human remains to develop products and train doctors on them. Some, including Aurimar’s, were used for both.

Donated bodies play a key role in medical education and the biotechnology industry, helping surgeons build their skills and researchers develop potentially lifesaving treatments. While using unclaimed bodies for this purpose remains legal in much of the country, including Texas, it’s widely viewed as unethical because of the absence of consent and the pain it can inflict on survivors.

Reporters have identified two dozen other cases in which families learned weeks, months or years later that a relative’s body had been provided to the Health Science Center. Eleven of those families only learned what happened from NBC News and Noticias Telemundo — including five, in addition to Aurimar’s loved ones, who were horrified to find their relative’s names on the list of unclaimed bodies published by the news outlets this fall.

In response to NBC News’ findings, the Health Science Center suspended its body donation program, fired the officials who ran it and pledged to stop using unclaimed bodies. Spokesperson Andy North did not answer questions about Aurimar’s case, but said in a statement to reporters that the center extends apologies to all the “individuals and families impacted” and has “taken multiple corrective actions.”

In many of the cases NBC News uncovered, the people whose bodies went unclaimed were homeless, struggling with drug addiction or estranged from their families.

Aurimar was none of these. She was in constant touch with her mother — speaking to her just hours before she died. Her family immediately scrambled to scrape together the thousands of dollars it would have cost to have her body repatriated to Venezuela, believing falsely month after month that her remains were preserved in a Dallas morgue.

Instead, what followed were a cascade of bureaucratic breakdowns and communication failures. The Dallas County Medical Examiner’s Office had Arelis’ cellphone number on file, but there’s no record in documents obtained by NBC News that the agency attempted to call her before declaring Aurimar’s body abandoned. The agency declined to comment.

Throughout this ordeal, Arelis has struggled — from a home with no internet, in a country with no diplomatic ties to the U.S. — to reclaim her daughter’s body.

Until then, she said, she can’t truly begin to mourn.

“Every night I say, ‘My God, why did you take my daughter?’” she said. “I don’t accept my daughter’s death. Not yet.”