Now Reading: Bird Flu Updates: Virus Mutation in First U.S. Severe Human Case May Increase Transmission in People

-

01

Bird Flu Updates: Virus Mutation in First U.S. Severe Human Case May Increase Transmission in People

Bird Flu Updates: Virus Mutation in First U.S. Severe Human Case May Increase Transmission in People

The virus in the first severe human bird flu case in the United States was found to have mutated, likely making it more transmissible to humans, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) said. The patient, who was hospitalized earlier this month, was likely infected after being exposed to sick and dead birds in a backyard flock in Louisiana, the CDC said. A genetic analysis of samples from the patient found mutations in the virus that weren’t found in the birds. “The changes observed were likely generated by replication of this virus in the patient with advanced disease rather than primarily transmitted at the time of infection,” the CDC said this week. The agency called the mutations “concerning’ and “a reminder that A(H5N1) viruses can develop changes during the clinical course of a human infection.” But it said the case would be more concerning if the mutations had been found in the birds or at an earlier stage of infection when the patient is more likely to unknowingly spread the virus. While the Louisiana patient is the first person in the U.S. to contract a severe case of bird flu, more than 60 milder cases have been reported this year. Meanwhile, a big cat sanctuary in Washington recently suffered “significant losses” among its animals after a bird flu outbreak.

Follow Newsweek’s live blog for updates.

Avian influenza A viruses and human infections

According to the CDC, avian influenza A viruses infrequently infect humans. Five subtypes—H5, H6, H7, H9, and H10—have been linked to human infections, with H5, H7, and H9 being the most common culprits. Notably, A(H5N1) and A(H7N9) have accounted for the majority of reported cases, while HPAI A(H5N6) and LPAI A(H9N2) have also caused infections in recent years.

Other subtypes, including A(H6N1), A(H10N3), A(H10N7), and A(H10N8), have occasionally infected small numbers of people. In the U.S., no cases of HPAI A(H7) virus infections have been recorded, though there have been four confirmed cases of LPAI A(H7N2) infections.

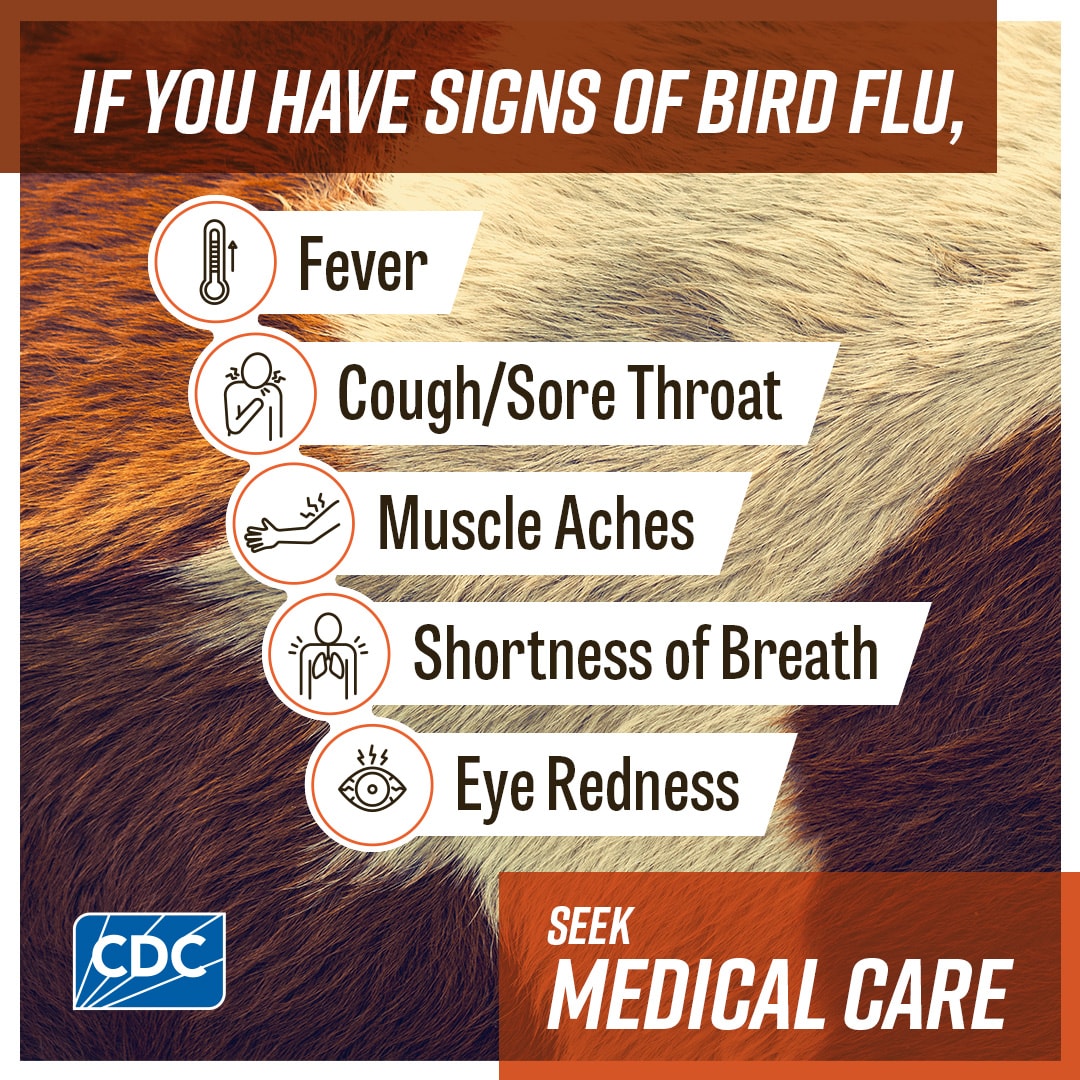

If you have any of these signs of bird flu, seek medical care

If you have these signs of bird flu, seek medical care, CDC graphic

CDC

The CDC have released a list of bird flu symptoms including fever, muscle aches and eye redness.

“If you have signs of bird flu, seek medical care,” the agency warned.

CDC launches free vaccination program to protect farmworkers

The CDC has launched a free vaccination program to protect farmworkers from bird flu.

More than 100,000 doses of the annual flu vaccine were provided across 12 states suffering from bird flu outbreaks.

The flu vaccine does not protect workers against bird flu but prevents co-infections and possible mutations of the virus if they catch the virus while already suffering from seasonal flu.

Eduardo Azziz-Baumgartner, a Medical Epidemiologist with the CDC, told ABC News, that people in rural communities typically get the flu vaccine less often than other parts of the U.S.

“This year, there’s also concern about the bird flu,” he said. “We certainly don’t want people to have co-infections with the two viruses.

“It can lead to changes in the virus that can be problematic and for getting the ability to transmit among people.”

There are currently no human vaccines available to prevent HPAI A(H5N1), the highly contagious and deadly strain of the influenza A virus that causes bird flu.

There are vaccines in development, including one from Moderna, and plans in place for a potential pandemic.

Understanding the classifications of avian influenza A viruses

Avian influenza A viruses are divided into two categories—low pathogenicity (LPAI) and highly pathogenic (HPAI)—based on molecular characteristics and their impact on chickens in laboratory settings, according to the CDC.

Low Pathogenic Avian Influenza (LPAI): These viruses cause mild or no illness in poultry, such as ruffled feathers or reduced egg production. While most avian influenza A viruses are LPAI, some can mutate into more severe forms.

Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI): HPAI viruses lead to severe disease and high mortality in poultry, often killing 90%-100% of infected chickens within 48 hours. While ducks can carry the virus without symptoms, HPAI infections in poultry can spread to wild birds, facilitating further geographic spread during migration.

Both LPAI and HPAI can quickly spread in poultry flocks, and their designation does not determine illness severity in humans, as both types have caused varying symptoms in infected individuals.

Genetic lineages of avian influenza A viruses

Avian influenza A viruses in birds have evolved into distinct genetic lineages based on their geographic origins, according to the CDC. For example, viruses first detected in Asia are genetically different from those first identified in North America.

Researchers analyze the genetic make-up of these viruses to classify them into broad lineages, which can be further refined by comparing closely related strains. Lineage names often include details about the host, time period, and location to provide more specific distinctions. This detailed genetic analysis helps scientists track and understand the evolution and spread of avian influenza A viruses.

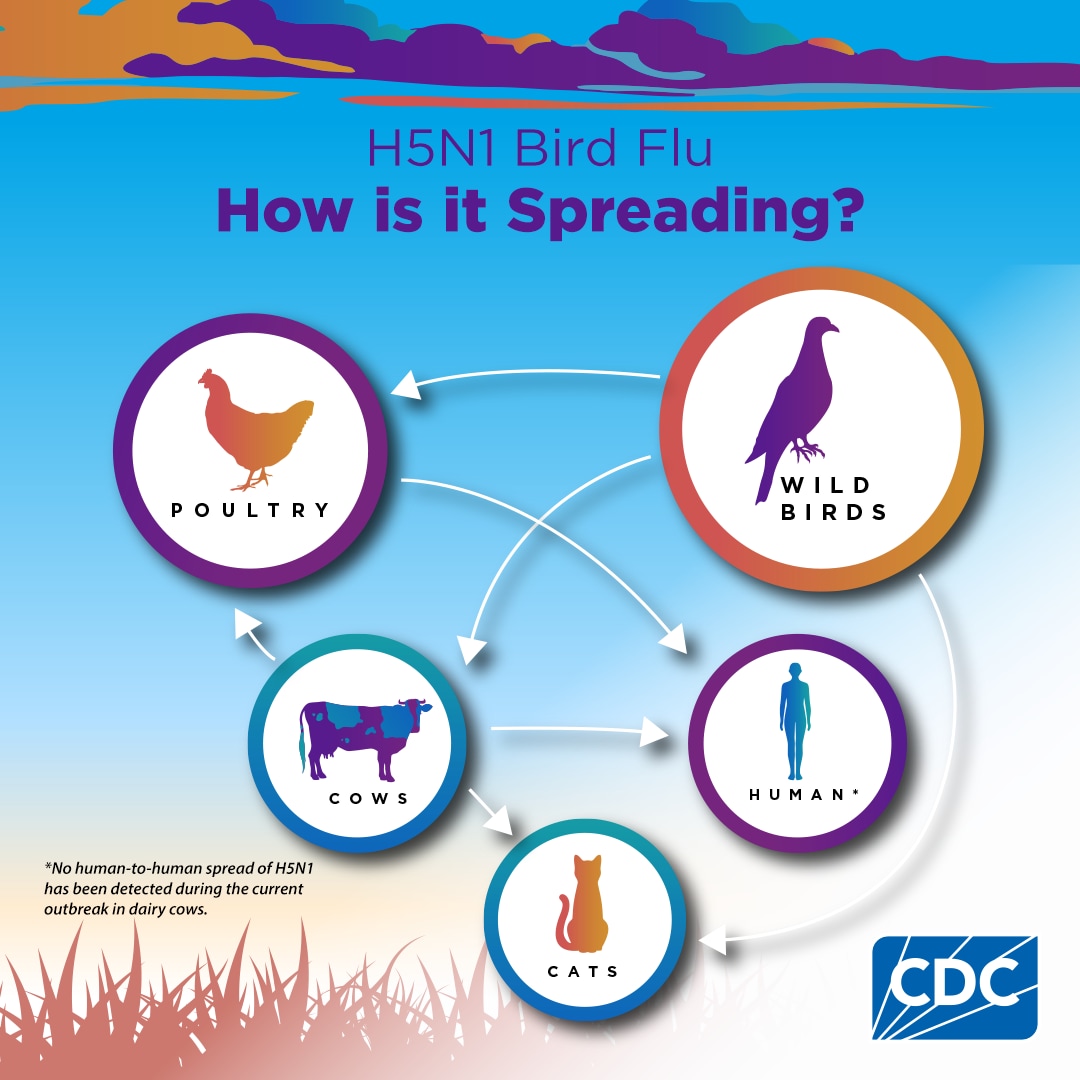

How is bird flu spreading?

How is bird flu spreading? CDC graphic shows how the virus is spreading between species

CDC

Influenza A subtypes and their impact across species

A woman with the flu sits on her sofa under a blanket and blows her nose with a tissue, with an image of a flu virus inset. A virus is a microorganism that can cause…

SciePro / dragana991/iStock / Getty Images Plus / Canva

Influenza A viruses are classified into subtypes based on two surface proteins: hemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase (NA), with 18 known HA subtypes and 11 NA subtypes. According to the CDC, most subtypes are found in birds, except H17N10 and H18N11, which are exclusive to bats. Combinations like H7N2 or H5N1 indicate specific HA and NA protein pairings.

Among humans, only two subtypes—A(H1N1)pdm09 and A(H3N2)—are actively circulating, while influenza A viruses are also known to infect species like horses, dogs, and swine. Although avian influenza A viruses occasionally infect other animals such as seals and cats, they rarely spread widely among these populations.

Bird flu ‘wake up call’: Scientists issue warning after mutation

Scientists are warning the public about bird flu after a patient in Louisiana showed mutations that could increase the transmission of the virus.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention analyzed samples from a patient with the nation’s first severe case of bird flu. The agency found mutations that were not found in virus sequences collected on the patient’s property, “suggesting the changes emerged in the patient after infection,” it announced on its website on Thursday.

Experts—including Michael Mina, a physician-scientist, and Rick Bright, an immunologist and a virologist—have since commented on the news.

Newsweek has contacted Mina and Bright for further comment via social media.

The immune system’s powerful reaction to viral infections

Stock image. The immune system combats viral infections by triggering fever and chills, which help the body fight off harmful microbes, with moderate fevers linked to better recovery outcomes.

Photo by Jacob Wackerhausen / Getty Images

When bodily cells are damaged by viruses, the immune system activates, leading to symptoms like fever and chills. According to Pfizer, fever is generally a protective response, raising the body’s temperature to combat invading microbes.

Research shows that patients with mild to moderate fevers in intensive care often fare better than those without a fever or with extreme temperatures. Chills, which frequently accompany a fever, occur as the body increases its core temperature to fight infection. These immune responses are vital in the body’s battle against viral invaders.

The way viruses replicate and spread within the body

Once inside a host, viruses latch onto cell surfaces, where their proteins bind with cellular receptors. This fusion allows the virus to release its DNA or RNA into the host cell, initiating reproduction. If the immune system fails to neutralize the invading virus, infection takes hold, according to Pfizer.

The virus may remain localized at its entry site or spread to other cells and tissues through the bloodstream, enabling widespread infection. In some cases, viruses travel via nerve endings to attack the nervous system or infiltrate major organs, further complicating the host’s ability to fight the infection. Understanding these processes is critical in developing antiviral treatments and preventative measures.

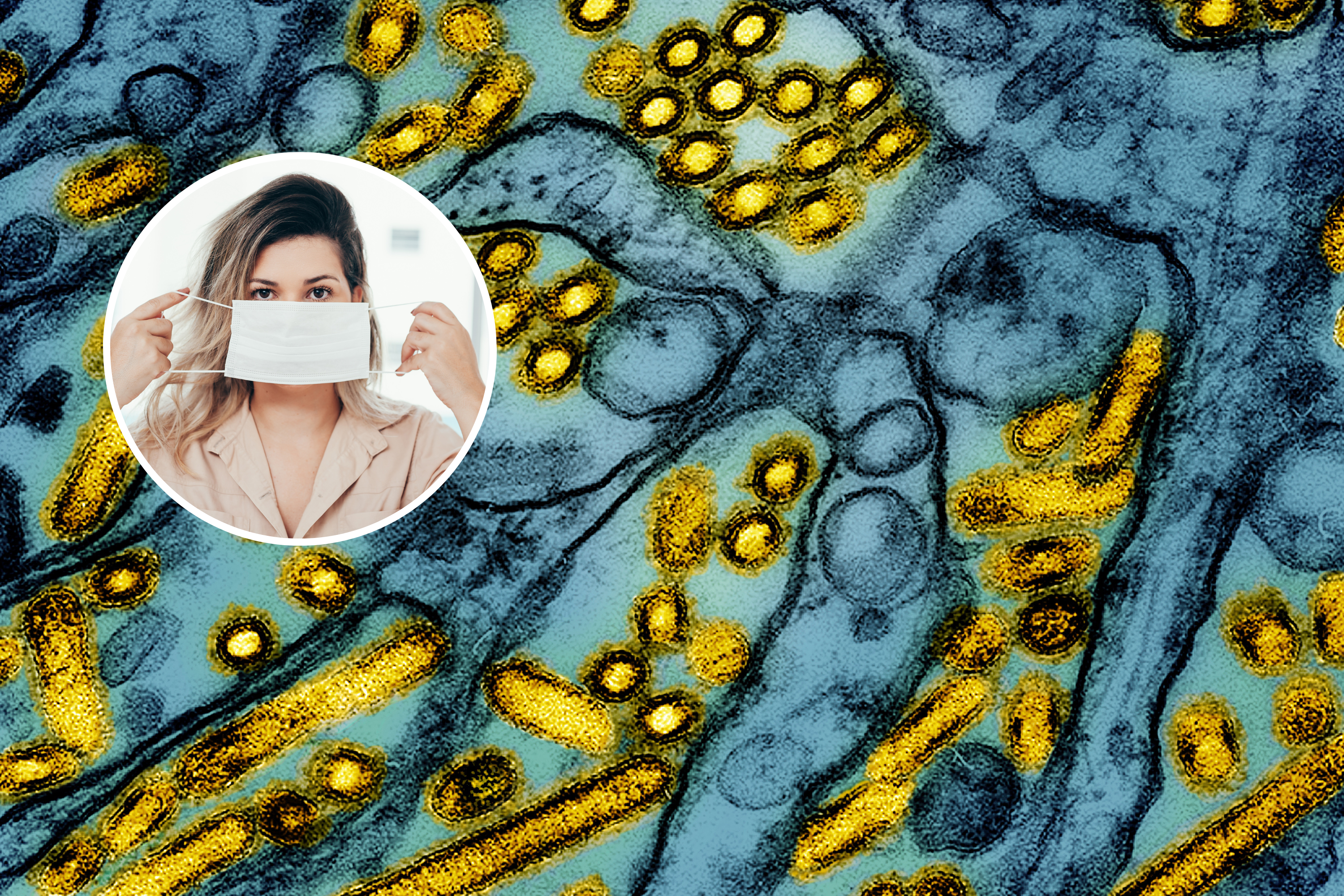

How viruses infiltrate the body

A colorized electron microscope image released by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases on March 26, 2024, shows avian influenza A H5N1 virus particles in yellow (main) and a person putting on a…

CDC/klebercordeiro/NIAID via AP/Getty

Viruses, which cannot reproduce on their own, rely on host cells to replicate, making them highly adept at penetrating and infecting the human body. According to Pfizer, viruses most commonly enter through the respiratory tract, including the nose and mouth, making this the primary route for pathogens such as rhinoviruses, coronaviruses, and influenza viruses.

Other entry points include the alimentary canal, through activities like eating or drinking, where enteroviruses may find access. The urogenital area serves as a route for viruses such as HIV, hepatitis, and herpes during sexual activity. Additionally, viruses can infiltrate through the surface of the eyeball or through breaks in the skin, as intact skin acts as a barrier they cannot breach.

Mucus linings in areas such as the throat, gastrointestinal tract, and genital tract provide some protection, but persistent viruses can often bypass these defenses to infect the host. Understanding these entry mechanisms is key to developing strategies for prevention and treatment.

Understanding viral transmission in indoor spaces

The spread of viruses in indoor environments is influenced by a range of factors, including environmental conditions such as temperature, humidity, and space usage, as well as the activities of the people within those spaces, according to the American Society for Microbiology.

Actions like flushing toilets, eating, talking, and vacuuming can contribute to viral transmission, along with the intrinsic properties of viruses themselves, such as surface charge and the presence of a viral envelope.

“It’s not a simple matter, but really a complex ecology of how viruses survive in the environment,” said Charles Gerba, Ph.D., a virology professor at the University of Arizona’s Water & Energy Sustainable Technology Center.

While each indoor space has a unique transmission dynamic, key avenues like aerosol dissemination and surface interactions play critical roles in the spread of pathogens.

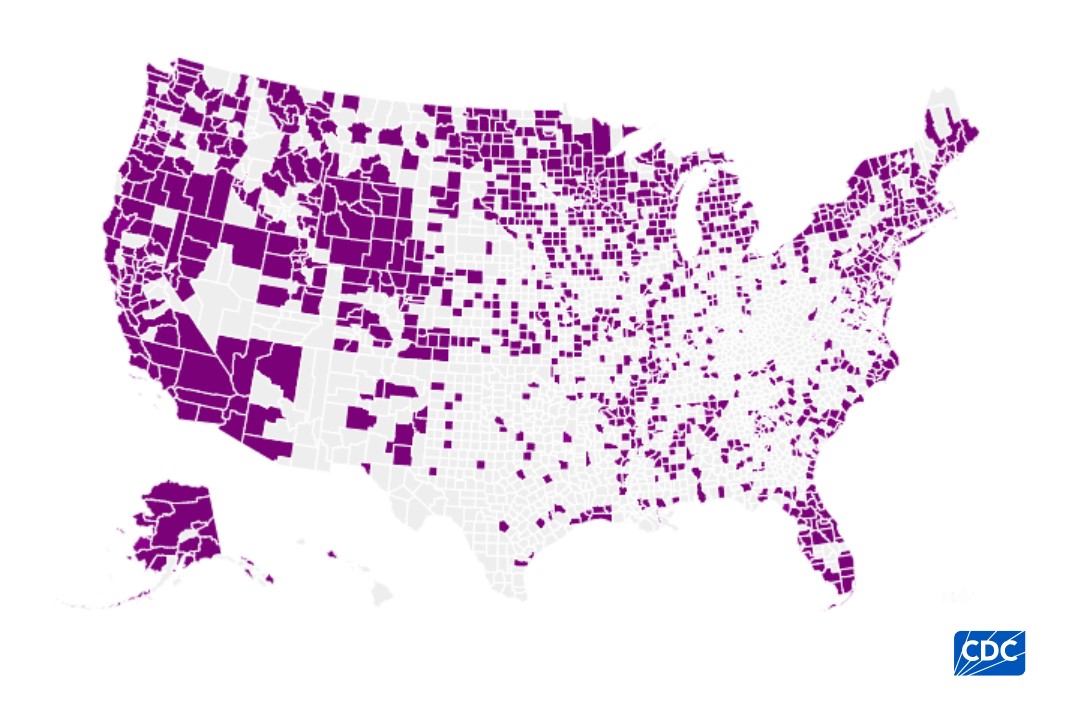

Map shows avian flu cases in wild birds across U.S.

This map shows detections of highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) A(H5) viruses in wild birds in the United States since 2022. This data is provided by U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) Animal and Plant Health…

CDC

A map, from the CDC, shows avian flu outbreaks in wild bird populations across the United States.

This data, provided by U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS), reveals just how widespread the virus is with a vast number of counties reporting bird flu cases.

Map shows bird flu cases in commercial poultry and backyard flocks

This map shows bird flu outbreaks involving commercial poultry facilities, backyard poultry and hobbyist bird flocks in the United States. This data is provided by U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) Animal and Plant Health Inspection…

CDC

A map, from the CDC, shows bird flu outbreaks in commercial poultry facilities, backyard poultry and hobbyist bird flocks across the United States.

The data, provided by U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS), records 127,470,312 cases of highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) A(H5) viruses detected in U.S. wild aquatic birds, commercial poultry and backyard or hobbyist flocks since January 2022.

How to protect your pet from bird flu

Stock image of cat. The random cat appeared in the woman’s bedroom prompting her to ask the internet for advice.

krblokhin/iStock / Getty Images Plus

As cases of bird flu increase, experts are urging pet owners to remain vigilant and take precautions to safeguard their animals from the disease.

Bird flu, or Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI), caused by viruses such as H5N1 and H5N8, spreads primarily through contact with infected birds, their droppings, or contaminated surfaces.

While human-to-pet transmission is rare, pets including cats and dogs can become infected if they come into close contact with infected birds or consume raw meat from infected poultry.

Pets are naturally curious, and this could put them at risk. It is important to minimize their exposure to wild birds and areas where infected birds might be present.

Tips for preventing HPAI infection in dogs and cats are the same as for many other infectious diseases, according to AVMA:

- Keep cats indoors.

- Keep pets that do go outdoors away from wild birds, poultry, and cattle and their environments.

- Prevent pets from eating dead birds or other animals.

- Avoid feeding pets raw meat or poultry and unpasteurized milk.

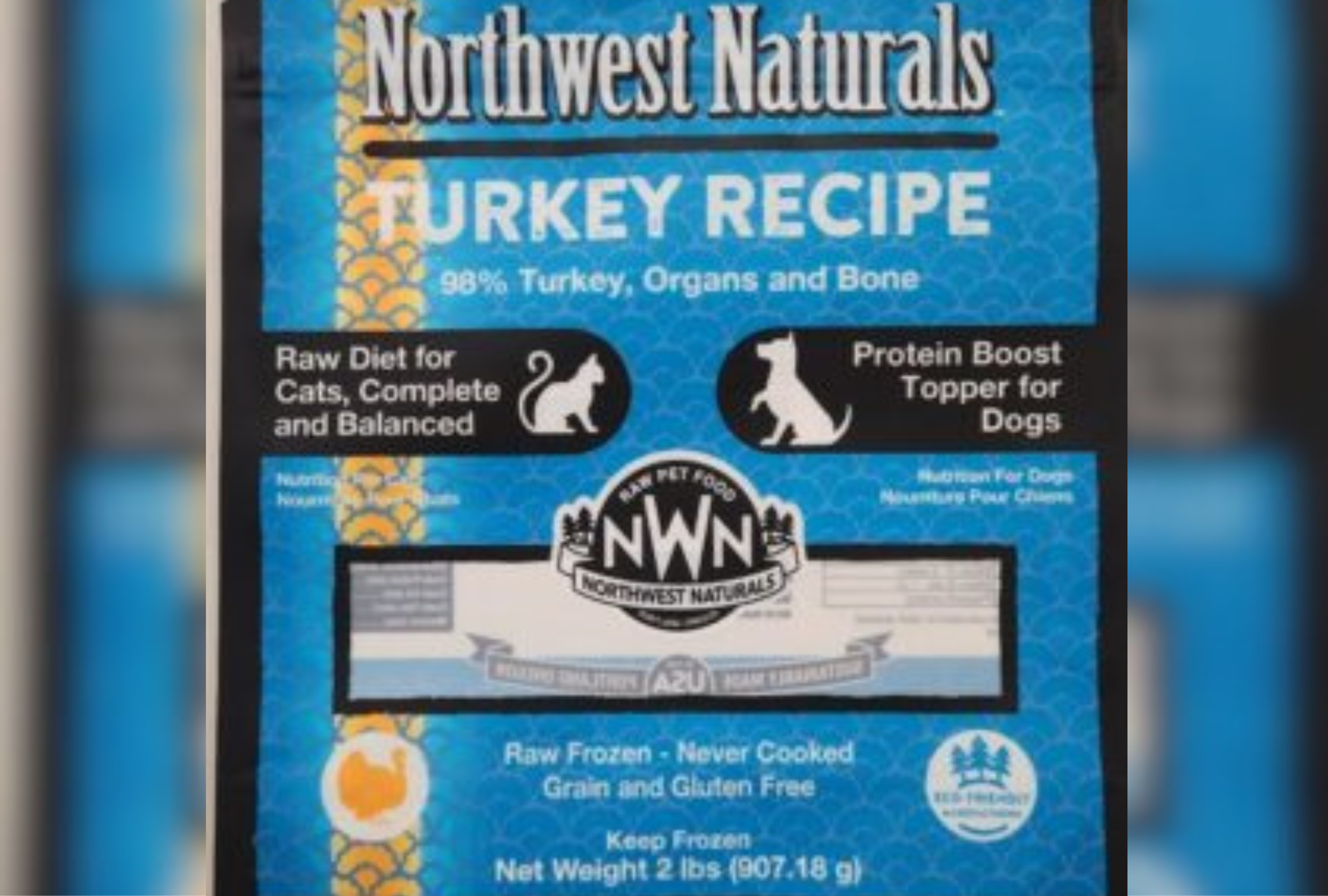

Urgent recall for pet food contaminated with bird flu after cat dies

Northwest Naturals has recalled one of its products after it has tested positive for Bird Flu. The contaminated product caused a cat to die.

Northwest Naturals

A Portland-based pet food company has issued a voluntary recall after a pet cat in Oregon died from eating one of its products, which was positive for bird flu contamination.

Northwest Naturals announced in a press release this week that it was “voluntarily recalling one batch” of its 2-pound Feline Turkey Recipe, raw frozen pet food after it had tested positive for avian influenza (HPAI) virus, or bird flu.

“Consumption of raw or uncooked pet food contaminated with HPAI can cause illness in animals,” the press release said. “To date, one case of illness in a domestic cat has been reported in connection with this issue.”

The recalled product is in 2-pound plastic bags with best if used by dates of May 21, 2026 and June 23, 2026. The food was sold through distributors in Arizona, California, Colorado, Florida, Georgia, Illinois, Maryland, Michigan, Minnesota, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island and Washington. It was also sold in British Columbia in Canada.

Consumers who have purchased the recalled product should immediately discard it and contact the place of purchase for a full refund, according to Northwest Naturals.

For additional information or questions, customers may contact Northwest Naturals of Portland at info@nw-naturals.net or 866-637-1872 from 7 a.m. to 3:30 p.m. PST, Monday through Friday.

Deadly Bird Flu Devastates Big Cat Sanctuary

A big cat sanctuary in Washington has suffered “significant losses” among the animals in its care after what it said was an outbreak of highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI)—also known as bird flu.

Newsweek contacted the Wild Felid Advocacy Center of Washington for further comment outside of standard working hours.

The Wild Felid Advocacy center of Washington said that the “devastating” viral infection, spread by wild birds is primarily transmitted through respiratory secretions and direct contact between birds.

Carnivorous mammals, including cats, can also contract the virus by consuming infected birds or their byproducts, it said, adding that cats are especially susceptible, with the infection often presenting mild initial symptoms, but rapidly advancing to severe pneumonia-like conditions that can lead to death within 24 hours.

According to a post from the sanctuary, 20 of their big cats have died.

CDC issues update on bird flu ‘mutations’ in humans

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has identified mutations in a strain of the avian influenza virus H5N1, also known as bird flu, found in a Louisiana patient.

The mutations were discovered after samples from the patient were analyzed, which marked the first severe case of bird flu in the U.S.

Newsweek has contacted the CDC for comment outside of standard working hours.

Earlier this month, the CDC confirmed that the first case of severe bird flu in the U.S., with CDC officials reporting the patient had been exposed to sick and dead birds in backyard flocks.

New outbreak of bird flu detected in Vermont

A new outbreak of bird flu has been detected in a backyard flock in Vermont, according to the state’s agricultural agency.

The flock of two dozen non-commercial birds in Franklin County was quarantined after the owner reported several bird deaths on December 19.

They were put down after bird flu was confirmed.

Everyone who came into contact with the infected birds are being closely monitored by the Vermont Department of Health. But so far, there have been no reported cases in humans in Vermont or New England from this current outbreak.

This is the fourth outbreak of bird flu in a domestic flock in Vermont since 2022, according to the announcement by the Vermont Agency of Agriculture, Food and Markets.

“Despite the low risk to the public, the virus remains deadly to many species of birds,” the agency said. “All bird owners, from those who own backyard pets to commercial farmers, are strongly encouraged to review biosecurity measures to help protect their flocks.”

Can you die from bird flu?

It is possible to die from bird flu. In the past, a human infection was likely to be serious—more than 50 percent of the nearly 1000 people infected with bird flu from the 1990s to 2020 died.

However, more recent cases of bird flu have generally been mild, with only one of the 61 cases in the U.S. experiencing severe symptoms requiring hospitalization.

“The fact that we’re seeing a greater proportion of mild cases in the current outbreak (since 2020) may reflect a change in the virus, but it might just be because we’re monitoring it more carefully and picking up mild infections that would previously have been missed,” Professor Ed Hutchinson, virologist at the University of Glasgow, Scotland, told Newsweek.

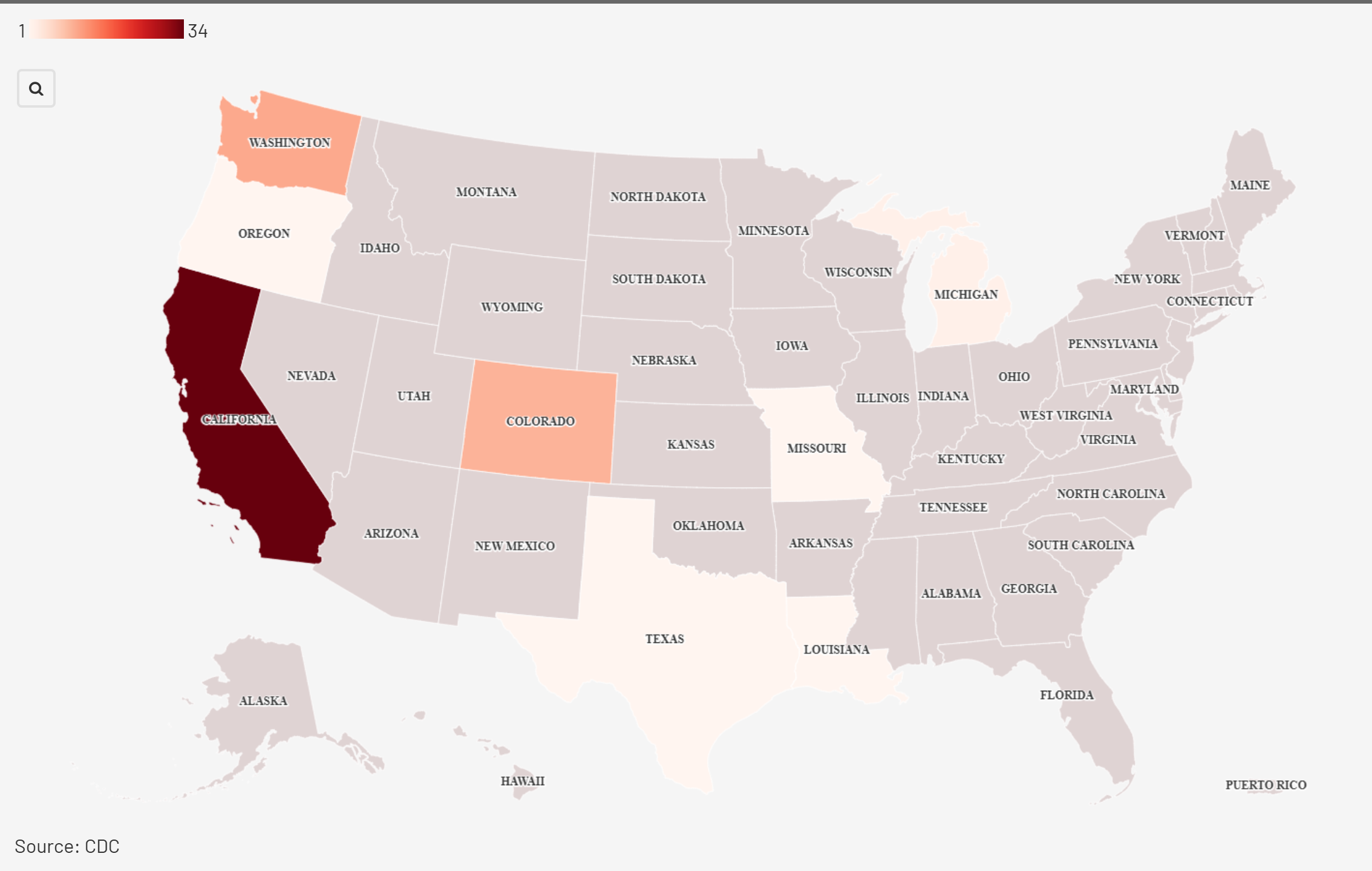

Bird flu outbreak map shows states with most cases

Map showing which states have the most bird flu caes recorded in humans.

Flourish

Newsweek has created a map showing which states have recorded the most human bird flu cases, after the first human case of severe bird flu was confirmed in Louisiana.

California, which has declared a state of emergency in response to the current outbreak, has recorded the most cases (34), followed by Washington (11) and then Colorado 10).

More than 60 bird flu infections have been reported this year, more than half the cases occurring in California. In two instances—an adult in Missouri and a child in California—health officials have yet to determine how the individuals were infected.

Previous cases in the U.S. have been mild, the vast majority occurring among farmworkers who had direct exposure to sick poultry or dairy cows.

But the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) confirmed the first case of severe bird flu in the country earlier this month. The patient had been exposed to sick and dead birds in backyard flocks.

Will bird flu become a pandemic?

The risk of a bird flu pandemic depends on whether the virus stays primarily an animal disease, with occasional spillover infections, or mutates to be a human illness.

“If we start to get human-to-human transmission, especially going into the winter in the U.S. when flu spreads the best anyways, there is a very high chance that this virus would start to spread,” Jeremy Rossman, senior lecturer in virology at University of Kent, previously told Newsweek. “We just don’t know what that would look like and that is the biggest concern.”

Professor Moritz Kraemer, a biologist specializing in pandemics at the University of Oxford, previously told Newsweek: “The fact that we are only a single mutation away from H5N1 (clade 2.3.4.4.b) potentially shifting from avian to human specificity underscores the importance of continued surveillance and control efforts to reduce the risk of pathogen spillovers.”

Hutchinson said: “When an influenza virus from a different animal adapts to spread effectively among humans, the result is a pandemic.

“At the moment, there is no indication that this has happened for H5N1, and we do not really know enough about this new H5N1 strain to confidently assess how likely it is to make that jump.

“But the more encounters the virus has with humans, the more chances it has to adapt to growing in them, and if it can mix and match its genes with a human seasonal flu, that could accelerate this process.”

Virologist warns of ‘grim’ bird flu situation

A graphic of a mutating virus with an image of a chicken overlayed.

poco_bw / wildpixel/iStock / Getty Images Plus / Canva

A virologist has warned that the “explosion” in human bird flu cases, including the first severe case in the U.S., increases the chances of a new pandemic.

“The H5N1 situation remains grim,” Dr. Angela Rasmussen, a virologist at the Vaccine and Infectious Disease Organization at the University of Saskatchewan, Canada, said in a post on Bluesky on Thursday.

“There has been an explosion of human cases, both of this genotype (D1.1) and the cow genotype (B3.13). More sequences from humans is a trend we need to reverse—we need fewer humans infected, period.”

“We don’t know what combination of mutations would lead to a pandemic H5N1 virus and there’s only so much we can predict from these sequence data. But the more humans are infected, the more chances a pandemic virus will emerge.”

There were 65 confirmed cases of bird flu in humans in the United States this year, according to the CDC.

Who is most at risk for contracting bird flu?

Those who are most at-risk of infection are poultry workers.

As the virus can spread to other animals, dairy workers are also at risk, as well as people who work with wild animals.

While people cannot catch bird flu from fully cooked eggs or poultry, people who consume raw milk are at higher risk of catching the flu from an infected animal.

What the CDC has said about the virus mutation

The exterior of the Center for Disease Control (CDC) headquarters is seen in Atlanta, Georgia. The CDC has issued an update on bird flu “mutations” found in a human patient.

Jessica McGowan/Getty Images

The CDC has said while the mutation in the human patient was “concerning,” it has not detected any transmission from the patient to other people, meaning that the risk to the general public remains low.

In a series of statements, the CDC said, “The changes observed were likely generated by replication of this virus in the patient with advanced disease rather than primarily transmitted at the time of infection

“Although concerning, and a reminder that A(H5N1) viruses can develop changes during the clinical course of a human infection, these changes would be more concerning if found in animal hosts or in early stages of infection.

“Overall, CDC considers the risk to the general public associated with the ongoing U.S. HPAI A(H5N1) outbreak has not changed and remains low.

“The detection of a severe human case with genetic changes in a clinical specimen underscores the importance of ongoing genomic surveillance in people and animals, containment of avian influenza A(H5) outbreaks in dairy cattle and poultry, and prevention measures among people with exposure to infected animals or environments.”

How does bird flu spread to humans?

Broiler chickens eat food close-up on a poultry farm. People who work with poultry, or other animals, or who are regularly in close contact with them, are more at risk of contracting bird flu, although…

Kalinovskiy/iStock / Getty Images Plus

H5N1 is one of the more common bird flu strains to make the jump from birds to humans.

The infected birds spread the virus through their saliva, mucus and feces. If these get into a human’s eyes, nose or mouth, or is inhaled, then they can become infected.

Virus particles could be in the air or on something touched by a person.

Common ways it is spread is by someone touching contaminated bedding and touching their face, or handling a sick bird or touching bird feces and then failing to thorough wash their hands before eating.

The risk of infection from bird flu remains low for most people. It cannot be caught by eating fully cooked poultry or eggs.

The CDC said that spread from person-to-person is rare, but that the possibility exists for it to adapt and spread more easily.

Some scientists have warned that the virus may be able to jump to humans via cats.

What are the symptoms of bird flu?

In birds, symptoms of the infection include low energy and appetite, purple discoloration or swelling of body parts, fewer or misshapen eggs, a lack of coordination, and nasal discharge, coughing or sneezing.

In humans, bird flu presents itself in different ways, but the signs can appear more rapidly.

They include high fever, shivers, aching muscles, headache, coughing, shortness of breath, fatigue, and a runny nose.

More severe symptoms include nausea or belly pain, vomiting, diarrhea, pneumonia, chest pain, changes in organ function, or bleeding from the nose and gums.

What is bird flu?

The H5N1 strain of the influenza virus, also known as avian influenza or bird flu, takes many forms and is widespread among wild and domesticated birds.

Sick birds with a low-level infection tend to not show many symptoms. When infections are more severe, populations see higher mortality rates.

Health officials maintain that bird flu remains primarily an animal health concern as it can spread to domesticated poultry, pigs, horses and dogs.

Humans are also able to catch bird flu, although so far, there have been no documented cases of the virus spreading from person to person.