Now Reading: Charles Dolan, media pioneer and Cablevision founder, dies at 98

-

01

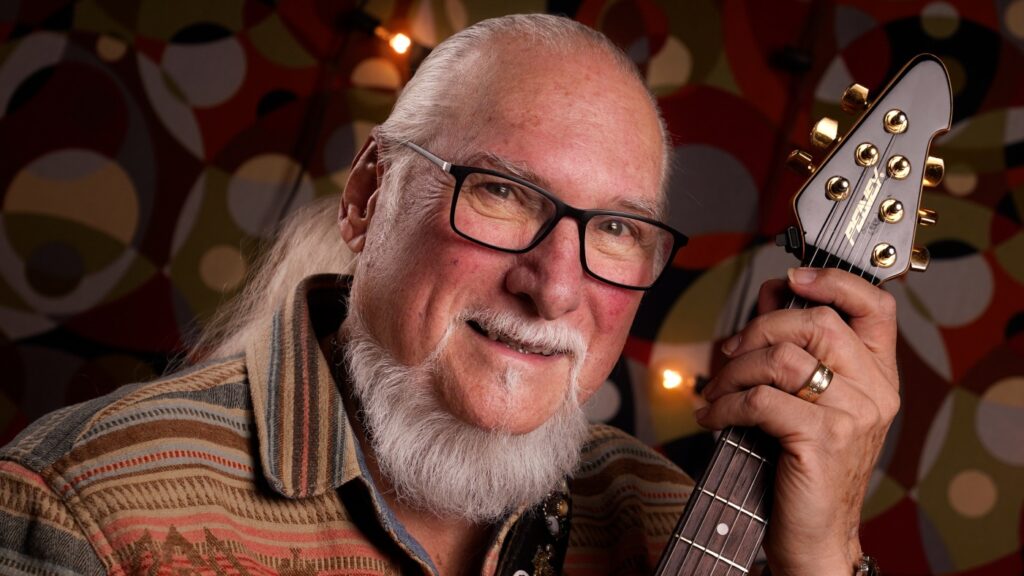

Charles Dolan, media pioneer and Cablevision founder, dies at 98

Charles Dolan, media pioneer and Cablevision founder, dies at 98

Charles F. Dolan, a media and telecommunications pioneer who founded Cablevision Systems Corp., has died, a family spokesperson said Saturday. He was 98.

Dolan first changed the landscape of television in the 1960s, when he laid cable in lower Manhattan and gambled that people would pay for programs superior to those broadcast for free over the air. He went on to found Home Box Office Inc., later known as HBO, American Movie Classics and launched the country’s first 24-hour cable channel for local news, News12.

“He’s one of the pioneers of cable television and one of the most brilliant people there is when it comes to programming and seeing what’s ahead,” Ted Turner, the founder of CNN, told Newsday in 1990.

On Saturday, the Dolan family, in a statement sent by a spokesperson, said, “It is with deep sorrow that we announce the passing of our beloved father and patriarch, Charles Dolan, the visionary founder of HBO and Cablevision.”

Dolan died Saturday of natural causes and was surrounded by his loved ones at the time of his death, according to the family.

“Remembered as both a trailblazer in the television industry and a devoted family man, his legacy will live on,” the family said.

Cablevision purchased Newsday Media Group in 2008. Newsday is now owned by Dolan’s son, Patrick Dolan.

The senior Dolan, whose primary home was in Cove Neck Village in Oyster Bay Town, expanded beyond television to own a controlling stake in companies that owned Madison Square Garden, Radio City Music Hall, the New York Knicks and the New York Rangers. The teams and sports and entertainment venues are now owned by The Madison Square Garden Company, whose CEO is Charles Dolan’s son James L. Dolan.

At the center of Charles Dolan’s holdings was Cablevision of Bethpage, which he founded in 1973 and built into one of the nation’s largest broadcasting companies.

Dolan passed day-to-day control of Cablevision to son James in 1995. But the senior Dolan remained chairman of the board until the company was sold to Altice in 2015 for nearly $18 billion.

Charles Dolan in 1979. Dolan had just announced a new cable network in Queens. Credit: Newsday/Dick Yarwood

Dolan had the reputation of being soft-spoken and reserved. He rarely granted interviews. And for years he eschewed chauffeurs and drove his own car, despite being one of the richest men in America.

He was married for 73 years to Helen Ann Dolan, who died last year. They have six grown children and lived on a 5-acre waterfront estate, where for decades they hosted annual July Fourth fireworks displays that attracted hundreds of onlookers who watched from boats in Long Island Sound.

Despite his courtly demeanor — he spoke so softly in meetings that people sometimes couldn’t hear him — Dolan had a reputation for pursuing deals with patient yet intense fervor, sometimes taking years to get what he wanted. Competitors said he waited decades for a chance to buy Madison Square Garden. When the opportunity arrived, he leapt with abandon.

“I call him bulldog Dolan,” former Univision chairman Andrew Jerrold “Jerry” Perenchio told the Los Angeles Times in 1994.

Dolan was born in Cleveland Heights, Ohio, one of four boys and the grandchild of Irish immigrants. His father, David J. Dolan, was an inventor who created a steering wheel lock to deter would-be thieves from making off with Model T Fords. He died of cancer in 1943, when Charles was 16, leaving him and his brothers to be raised by their mother.

By then, Charles Dolan was already pushing into the media business. He earned $2 a week writing a column on the Boy Scouts for the Cleveland Press.

Dolan worked at a radio station in high school, served briefly in the Air Force in the waning days of World War II, and returned to Ohio and enrolled at John Carroll University. It was there, in logic class, that he met his future wife, Helen Burgess.

Dolan quit college before graduating and started a sports newsreel business out of the couple’s apartment. Using their kitchen as a studio, Dolan and his wife pasted negatives on the cabinets and cobbled together highlight films that they would sell to stations across the nation.

The operation, however, made little money. Dolan sold the business to a competitor, Telenews, in 1952, essentially trading his customers for a job with the company in New York City. The Dolans moved east.

In 1954, Dolan took a job with Sterling Television, where he helped launch a project to wire Manhattan with coaxial cable to deliver news and tourism programs.

In the mid-1960s, cable television was a media backwater, confined to rural areas too remote for airborne signals. The conventional wisdom was that no one in a city or suburb would pay for television programs when they came free with an antenna.

“No one but Chuck Dolan ever thought cable would amount to anything outside poor reception areas,” said Perenchio, the former Univision executive.

In 1965, Dolan persuaded the New York City Board of Estimate — which at the time governed the five boroughs — to award him the franchise to wire the southern half of Manhattan. Dolan tapped Time Inc. and others for backing, then began the massive task of installing underground cable amid the warren of buildings. Once it was in place, Dolan’s company, Sterling Manhattan Cable, needed to find a way to attract subscribers. He turned to sports.

In 1967, he struck a deal with Madison Square Garden to offer Knicks and Rangers playoff games. At the time, home games were blacked out by regular television. So the only way to watch was having a seat at the Garden — or subscribe to Dolan’s system.

“I remember walking down Third Avenue, and every bar was filled to overflowing,” Dolan said in Wired to Win, a 2003 book about the early days of cable. “They were all wired for cable and showing the games people couldn’t see on regular broadcast television. It was wonderful.”

But profits were a long way off, and it would take more than sports to keep cable afloat. Dolan, who was deeply in debt, needed more money to develop programming with broader appeal. So in 1972, while aboard the Queen Elizabeth II for a family vacation, Dolan holed up in his cabin with an old typewriter and began to write.

As the ship steamed east toward France, he banged out the blueprint for a national pay-television channel that he hoped would convince Time Inc. — which already owned 20% of Sterling Manhattan Cable — to invest more money and take the company to the next level. He called it “The Green Channel.” America would come to know it as HBO.

The idea was to broadcast a mix of movies and sporting events and syndicate to other cable systems around the country. Time Inc. was impressed, and the channel launched in November 1972.

Nonetheless, Dolan’s company struggled to turn a profit. His relationship with Time Inc. soured. In 1973, Time Inc. bought out the company, including HBO. In exchange for relinquishing control, Dolan walked away with Time’s fledging cable system in Nassau County, with 1,500 subscribers.

“That was the beginning of Cablevision Systems Corporation,” Dolan said in the book “Wired to Win.”

Over the next decades, Dolan built his subscriber base, launched subsidiaries and developed programming, including the SportsChannel, American Movie Classics, Bravo and others. He expanded into Brooklyn, the Bronx, Connecticut, New Jersey and elsewhere.

He took Cablevision public in 1986 but maintained a majority stake.

“I have to admire the way Chuck has built his company and retained control,” Liberty Media Corporation chairman John C. Malone told the Los Angeles Times in 1994. “It’s really miraculous.”

In 1998, Dolan helped found The Lustgarten Foundation in Uniondale, after Cablevision vice chairman Marc Lustgarten was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer at age 51. The foundation is now the nation’s largest private supporter of pancreatic cancer research.

Dolan also served as a trustee of Fairfield University in Connecticut, where the business school is named after him. And despite never graduating from John Carroll University, he gave the school $20 million in 2000 to build a science and technology center.

Dolan is survived by sons Patrick Dolan, Thomas Dolan and James Dolan; daughters Marianne Dolan-Weber, Kathleen Dolan and Deborah Dolan-Sweeney; and19 grandchildren and five great-grandchildren.

Funeral arrangements were pending.

With James T. Madore, Joe Ryan and Dandan Zou