Human evolution’s biggest mystery, which emerged 15 years ago from a 60,000-year-old pinkie finger bone, finally started to unravel in 2025.

Analysis of DNA extracted from the fossil electrified the scientific community in 2010, when it revealed a previously unknown human population that had, in the distant past, encountered and interbred with our own species, Homo sapiens. This enigmatic group became known as the Denisovans after Denisova Cave in Siberia’s Altai Mountains, where the pinkie finger was found.

Despite intimate knowledge of this population’s genetic makeup, traces of which millions of people carry today, scientists knew nothing about the appearance of the Denisovans, or where they lived or why they disappeared. The discovery, and the questions it unleashed, galvanized a generation of geneticists, archaeologists and paleoanthropologists.

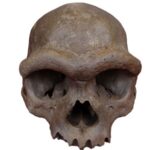

Some of that work paid off this year, and scientists at last put a face to the Denisovan name by extracting new clues from another well-known fossil: a prehistoric human skull that didn’t seem to fit with any known group. Now, other jigsaw pieces have begun to fall into place.

When the skull came to light in Harbin in northeastern China in 2018 after being stashed for safekeeping at the bottom of a well for decades, some scientists had a hunch that it might be Denisovan.

DNA sequences from the group had been detected in the genomes of present-day Asians, but not Europeans, suggesting that this region was where the Denisovans predominantly lived.

Based on its distinctive shape, the researchers attributed the skull to a newfound species they called Homo longi or “Dragon Man.” The dozen or so Denisovan fossils that had been identified since 2010 using DNA were too small and fragmentary to warrant an official species name.

Getting ancient DNA from the skull, which was estimated to be 146,000 years old, was the key to understanding whether there was a link between Dragon Man and the Denisovans. However, it proved to be tricky.

A team led by Qiaomei Fu, a geneticist and professor at the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, part of the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing, tested six bone samples from Dragon Man’s lone surviving tooth and the cranium’s petrous bone, a dense piece at the base of the skull that’s often a rich source of DNA in fossils. However, the samples yielded no results.

But Fu, who as a young researcher had been part of the team at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, that first discovered the Denisovans, reported in June that her team had been able to retrieve Denisovan genetic material from an unexpected source: Dragon Man’s dental calculus — the gunk left on teeth that can over time form a hard layer and preserve DNA from the mouth.

That information wasn’t a slam-dunk result. The genetic material researchers had retrieved was mitochondrial DNA, which, unlike nuclear DNA, is only inherited through the maternal line, providing an incomplete picture of an individual’s genomic ancestry. This finding meant, potentially, that Dragon Man could have been a mix of two species, something that’s not unprecedented. In 2018, scientists revealed a fossilized bone from Denisova Cave that belonged to a girl with a Neanderthal mother and a Denisovan dad.

However, the team also recovered protein fragments from the petrous bone samples, which — though less detailed than DNA — suggested the Dragon Man skull belonged to a Denisovan population.

Together, the two lines of evidence “cleared up some of the mystery surrounding this population,” Fu told CNN in June when the research was published. “After 15 years, we know the first Denisovan skull.”

The DNA finding makes it likely that Homo longi will become the official designation for the dozen or so other Denisovan fossils, Chris Stringer, a paleoanthropologist and research leader in human evolution at London’s Natural History Museum, said in an email.

Ryan McRae and Briana Pobiner, paleoanthropologists at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, agreed, although they said the name Denisovan would likely persist as a popular name, much like how most people call Homo neanderthalensis Neanderthals today.

“While more work needs to be done to build the body of evidence and give scientists a more complete view of Denisovan anatomy, habitat, and behavior, being able to link complete fossils with the molecular evidence is a huge step forward,” McRae and Pobiner wrote in an annual list of the top stories in human evolution.

Additional evidence could be in hand, waiting to be identified, researchers suggest, and with it 2026 could be set for more groundbreaking revelations.

A skull fossil, with its telltale bumps and ridges, can reveal a great deal about what an individual looked like, according to John Gurche, a paleoartist who creates reconstructions of ancient human ancestors for museums, including the Smithsonian and the American Museum of Natural History. He recreated Dragon Man’s face for National Geographic.

Assuming the Dragon Man skull belonged to a typical Denisovan individual, scientists said the ancient human would have had pronounced brow ridges, large teeth and lacked our high foreheads. But, if dressed in modern attire, this prehistoric relative may not have drawn too many stares on a subway train.

Gurche said that he uses known relationships between soft and bony tissue in humans and apes to recreate facial features, such as the breadth of the eyeball, dimensions of nasal cartilage and the thickness of soft tissue in some parts of the face. More challenging were features about which the skull “offers little information,” including the form of the lips and ears, and placement of the hair.

With molecular evidence now linking Dragon Man to the Denisovans, it will be easier for paleoanthropologists to identify other potential Denisovan remains, including skull fossils from sites in China that have long defied classification.

More revelations could come from another skull fossil discovered in China in 2022, which hasn’t been formally described in scientific literature. It’s the third skull to be unearthed at the site known as Yunxian in China’s Hubei province and is thought to date back around 1 million years. The other two craniums were found in 1990.

A digital reconstruction published in September of the second skull, which was badly squashed, from the site suggested it was an early ancestor of Dragon Man, meaning the lineage could have originated much earlier than previously thought.

The researchers’ wider analysis, based on the reconstruction and more than 100 other skull fossils, also significantly pushes back the timeline for the emergence of species such as our own, Homo sapiens, and Homo neanderthalensis, by 400,000 years.

However, the findings attracted some skepticism. More details about the third Yunxian skull would enable the team to test the accuracy of the reconstruction and its placement within the human family tree.

A 200,000-year-old tooth, similar in appearance to the molar still attached to Dragon Man’s skull, may be set to shake up what’s known about the Denisovans and the human family tree more broadly next year and beyond. Researchers found the tooth during an excavation of Denisova Cave in 2020.

Stéphane Peyrégne, a researcher at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, and his colleagues have since analyzed the molar and from it recovered a Denisovan’s full genome — a highly detailed set of genetic information that can reveal past genetic diversity and evolution.

It’s only the second time scientists have been able to sequence a “high coverage” genome from a Denisovan fossil — the first was from the finger fossil that revealed the Denisovans’ existence.

The scientists shared the genome analysis in October on what’s known as a preprint server, which allows study authors to post early versions of their work online, and is undergoing peer review by other researchers. Peyrégne declined to comment on the paper until it’s formally published next year. Stringer described the findings as “very important.”

The genome allows further investigation of Denisovan biological traits that may influence human health today. For example, a study published in August suggested that a Denisovan gene variant involved in the production of mucous and saliva may have helped Homo sapiens adapt to new environments.

The new genome is also much older than the first and allows geneticists to probe more deeply into Denisovan history and reconstruct relationships between different ancient populations.

The genome represents a Denisovan man who lived in a small group 200,000 years ago in Denisova Cave. The group’s analysis revealed that not only had his ancestors apparently interbred with early Neanderthals, but the individual also had ancestry from an unknown “super archaic” group for which there is currently no ancient DNA match.

McRae at the Smithsonian said traces of these “ghost lineages” have been found in the DNA of modern humans as well, and scientists aren’t sure who they are. They could represent other extinct hominins such as Homo erectus or Homo floresiensis, sometimes known as the “hobbit.”

“Or, it could represent hominins that we genuinely haven’t found in the fossil record. They’re ghosts until we have something to trace them back to,” he said via email.

Figuring out the identity of this group will be a fresh mystery for experts in human evolution to ponder in 2026.

Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with news on fascinating discoveries, scientific advancements and more.