Refresh

Tanning beds are especially harmful to skin, a new study in the journal Science Advances suggests.

The study analyzed the medical records of around 32,000 patients who had visited a dermatology clinic at Northwestern University. Of these, more than 7,000 reported using tanning beds.

The team looked at a subset of the tanners and compared them with folks who did not use tanning beds. After controlling for various factors, such as risk factors for the deadly skin cancer melanoma, the team found that using tanning beds multiplied the odds of developing melanoma by a factor of 2.85. There was also a subtle-sign of causality — a “dose-response” relationship whereby more tanning led to higher risk.

They also took biopsies from 11 of the tanning bed users in the study, who went to a “high risk” skin cancer clinic, as well as from six cadavers, who presumably had normal risk of skin cancer. They then looked for molecular signs of DNA damage in the skin. They compared those against data from a vast database of people, known as the U.K. biobank.

Tanning seemed to induce unique signatures of DNA damage that were somewhat different from those due to general sunlight exposure. And tanning beds exposed more of the skin to UV light, as well as exposing skin not typically exposed to high levels (presumably because people tan their whole body in such beds, versus wearing coverups or swimsuits outdoors).

Young people who tanned frequently also had more mutations in their skin than people who were twice their age, the study found.

“We found that tanning bed users in their 30s and 40s had even more mutations than people in the general population who were in their 70s and 80s,” study co-author Bishal Tandukar, a postdoc of dermatology at the University of California, San Francisco, said in a statement. “In other words, the skin of tanning bed users appeared decades older at the genetic level.”

Tia Ghose

Enormous genetic study groups psychiatric disorders

Live Science contributor Clarissa Brincat just covered the largest genetic analysis of psychiatric disorders to date. The study, which included data from more than 1 million people, found shared genetic profiles that unite different psychiatric disorders. Across 14 disorders — including anorexia, OCD, schizophrenia and ADHD — the analysis revealed five distinct groups that share similar genetics.

Some of these shared genetics point to shared biological mechanisms that may underpin the disorders. For instance, depression, PTSD and anxiety fell into one group that included genes associated with glia, the brain’s nonneuronal support cells. That may hint that glia play a key role in the manifestations of each of these disorders.

However, an expert told Live Science that it’s important to remember that correlation does not equal causation; a gene variant being linked to a given disorder doesn’t mean it’s a cause of that disorder. The genetics of psychiatric conditions are very complex, in that they interact with a person’s environment and their experiences. Additionally, the genes tied to disorders can also be tied to traits like creativity or intelligence — it’s not as if there’s a “depression gene” or “PTSD gene” that does only one thing.

Nicoletta Lanese

New pumpkin toadlet is so smol!

A newfound species of pumpkin toadlet has caught our eye. Researchers announced the discovery in the journal PLOS One mid-last week, but we think it deserves a shout-out today.

The frog lives in the mountains of southern Brazil and belongs to a group of miniaturized diurnal (awake during the day) frogs called Brachycephalus, some of which are pumpkin colored — hence the name, “pumpkin toadlet.”

The Brachycephalus genus boasts the smallest known vertebrate in the world: A species known as B. pulex, whose females average just 0.32 inch (8.15 millimeters) in length and whose males are even shorter, at 0.28 inch (7.1 mm), which is smaller than a human fingernail.

This latest addition to the pumpkin froglet clan is a bit bigger, with a body length of up to 0.53 inch (13.4 mm). The frog is bright orange, as you’d expect, but distinguishes itself from other pumpkin froglets with small amounts of green and brown at irregular points on its body.

The researchers who made the discovery want the frog’s territory in the Serra do Quiriri area of Brazil to be protected to safeguard its future, as well as other unique species that live there.

You’ve got to imagine that the researchers wanted this pumpkin toadlet study out closer to Halloween. Ah, well, it’s a winter treat.

3I/ATLAS Hulks out

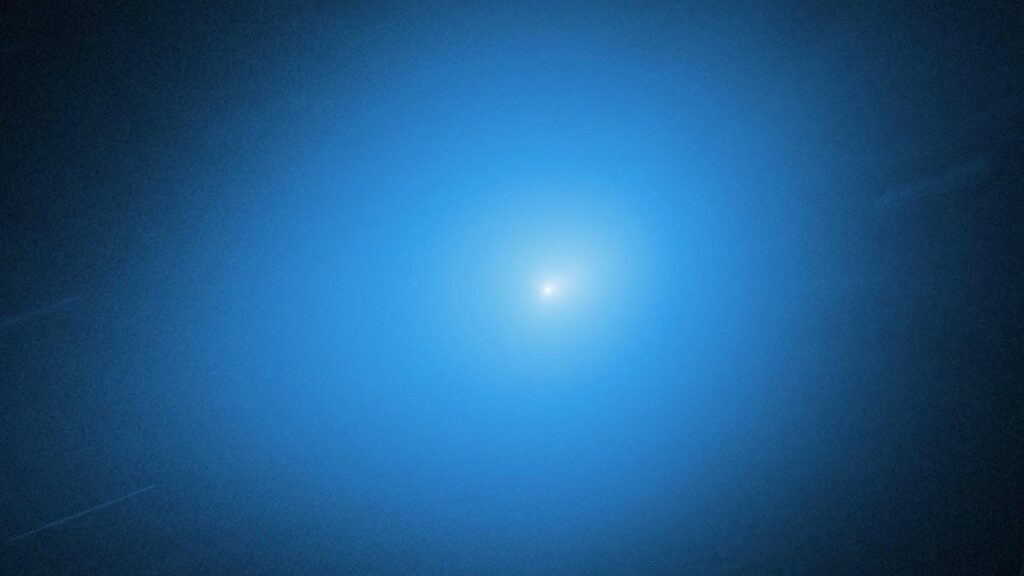

Speaking of 3I/ATLAS, Brandon reported on Friday (while the blog was down) that the interstellar comet is changing hues as it approaches Earth.

Atop Hawaii’s dormant Mauna Kea volcano, the Gemini North telescope confirmed that comet 3I/ATLAS has become greener and brighter since flying past the sun in late October.

Our home star heated up the interstellar object and, in doing so, made it much more active.

Find out what’s driving the comet’s greenish hue by reading the full story here.

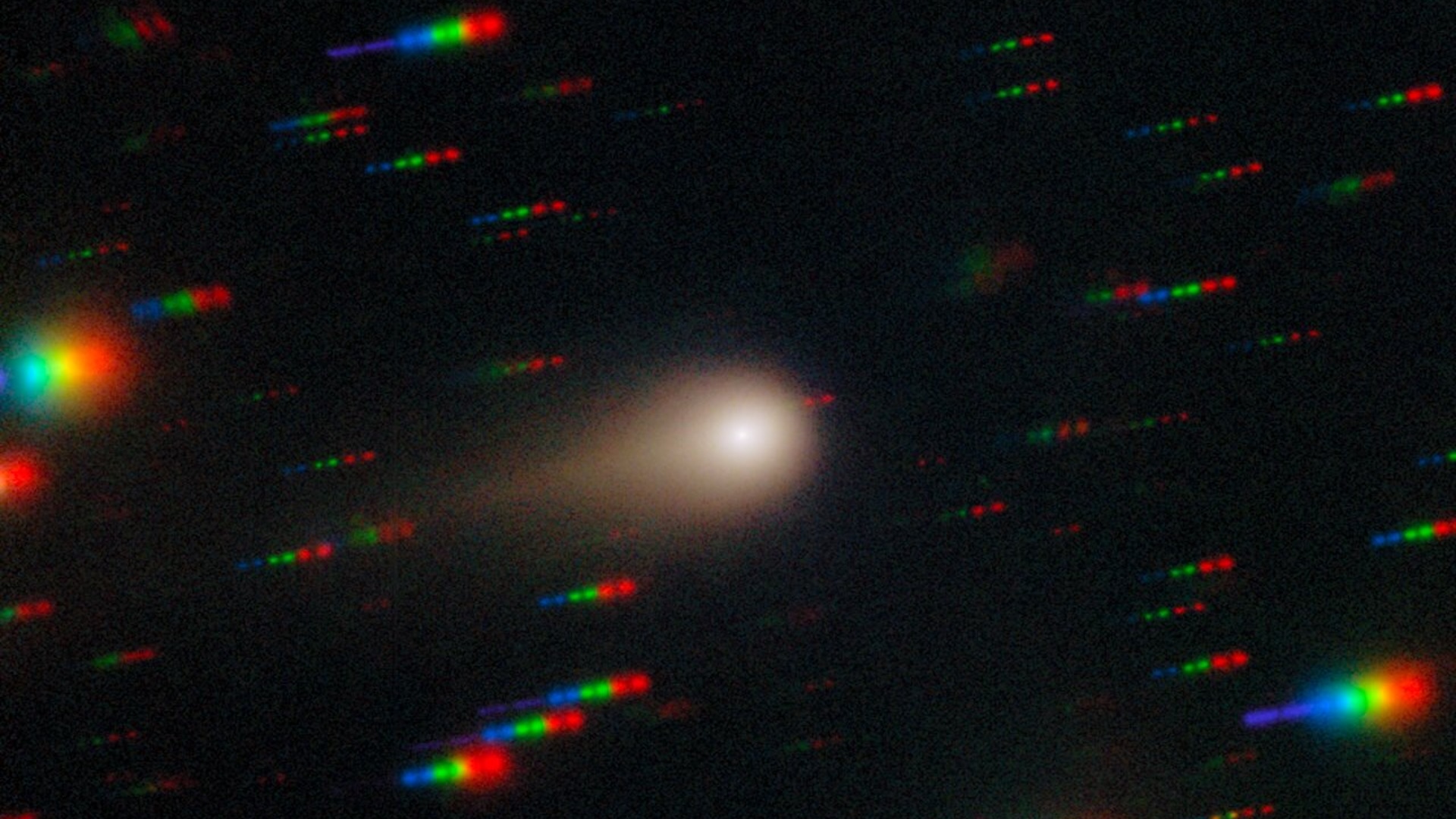

All eyes on 3I/ATLAS

The interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS makes its closest approach to Earth this week, coming within around 167 million miles (270 million kilometers) of our planet on Friday (Dec. 19).

Astronomers worldwide are studying the comet, which is only the third interstellar object ever recorded in our solar system and potentially the oldest comet ever seen.

But it’s not just space agencies getting in on the action. The United Nations’ International Asteroid Warning Network (IAWN) is about halfway through its 3I/ATLAS observing campaign, Live Science contributor Elizabeth Howell reports.

This is the first time that the IAWN network’s observing campaigns have tracked an interstellar object.

To learn why, read the full story here.

Geminid meteor shower gallery

The Geminids above Yosemite National Park in California.

A meteor zooms across the night sky above Ulanqab, Inner Mongolia, in China.

Back to Yosemite National Park for another striking meteor snap.

The Geminids above Yamdrok Lake in Tibet, China.

Here, a meteor appears as a horizontal dash across the night sky. This is the third photo taken by Tayfun Coskun at Yosemite National Park.

Geminids peak

Did you catch any meteors this weekend? The Geminid meteor shower peaked on Saturday night and Sunday morning in a near-moonless sky, making it perfect conditions for capturing the spectacle on camera.

The Geminids represent the most prolific meteor shower of the year. While the shower has been ongoing since Dec. 4, the best time to see its meteors was supposed to be overnight on Saturday through Sunday.

I didn’t see any because I was busy and unwilling to brave the cold. If like me you missed them too, we’ve still got a few more days to brave the elements — the Geminids will remain active until Dec. 20. I’ll also pull together a little gallery of some of the best images from the Geminids’ peak to mark the event.

If you want to learn more about the Geminids, check out our 2025 Geminids meteor shower guide by skywatching expert Jamie Carter.

Little Foot is a near-complete Australopithecus skeleton — the most complete ever discovered — from South Africa. Researchers first unveiled the small ancient human in 2017, but precisely where it sits on our family tree has been the subject of scientific debate.

Some have proposed that Little Foot is a previously unknown species and should be given the name Australopithecus prometheus. However, A. prometheus is a recycled name that was initially meant for another South African fossil discovered in 1948, but fell out of favour after researchers decided that the fossil was likely from the known species Australopithecus africanus. Another possibility was that Little Foot was also A. africanus.

The new claims derive from a study published last month in the American Journal of Biological Anthropology. Here, the research team argues that neither A. prometheus nor A. africanus is an appropriate classification for Little Foot.

The classification of human fossils is often contested, so I’m keen to see how other anthropologists react to the new study and will follow up with more information as it emerges.

Patrick Pester